Swedish Levant Company

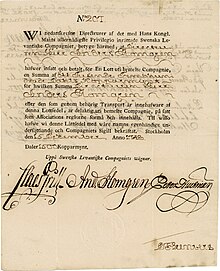

The Swedish Levant Company (Swedish: Levantiska kompaniet) was a Swedish chartered company founded on 20 February 1738 with the exclusive right to trade in the Levant for a period of ten years.[1]

Background

[edit]Following the surrender at Perevolochna, King Charles XII was exiled to Bendery in the Ottoman Empire.[2] It was during this time that Charles began to seek closer ties with the Ottomans, and Sweden's interest in the empire began to rise.[3]

The primary backer for trade with the Ottoman Empire was Swedish Board of Trade member Johan Silfvercrantz.[3] He proposed following the example of the English Levant Company to import goods such as silk while exporting Swedish products to the region.[3] Charles sent Silfvercrantz to the Levant to explore a future trade relationship, but he was unable to complete his work before his death the next year in 1712.[3]

In 1718, Charles died, and this marked the end of autocratic kingship in Sweden.[4] The subsequent Age of Liberty saw a shift of power from the crown to the Riksdag of the Estates.[4] It was at this time that Sweden had ambitions to expand its influence in the Mediterranean.[5]

In 1737, a trade agreement between the Ottomans and Sweden was signed.[6][3][7] A direct result of the treaty was the formation of the Swedish Levant Company.[7][8]

Founding

[edit]

The establishment of the company was a controversial issue.[3][7][10] Major issues included which powers the Riksdag should grant the company. Members of the Hat Party generally argued for the English Levant Company structure, but this strategy was criticized by some merchants who favored a freer Dutch method while trading with the Ottomans.[3]

The results saw a compromise between the parties.[7][8] The Swedish Levant Company had tax-free status for its exports, and it was granted duty-free status for all goods imported from the Levant coast. These imported goods would then be moved to auction for sale.[1] It was not granted a full monopoly on Mediterranean trade but instead limited to the Levantine coast. Additionally, private merchants could apply for a trading license from the company to conduct concurrent business.[7]

It had a starting capital of 200,000 daler silvermynt.[3][7] The two major shareholders of the company were Gustaf Kierman and Thomas Plomgren.[10][8] Unlike the earlier-formed Swedish East India Company, investment was limited to Swedish merchants only.[10]

Trade

[edit]Sweden had hoped to conduct a profitable trade with the Ottomans whereby it could export iron[3][11] and naval ammunition to Southern Europe.[11] In return, luxury goods would be imported into the country.[3]

Closure

[edit]The board of directors petitioned the Riksdag for the renewal of its charter, which was granted for an additional 10 years, until 15 January 1748.[1] However, the trading company saw the profits from its primary activity begin to languish.[1] The Private Committee in 1752 made recommendations to the Privy Council for the Riksdag to take additional measures to increase Levantine trade. This effort, however, failed; the company charter was officially revoked in 1756.[1][10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Westrin, Th., ed. (1912). Nordisk familjebok (Lee – Luvua) (in Swedish) (16 ed.). Stockholm: Project Runeberg. pp. 289–290. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ Tucker, S.C. (2010). A global chronology of conflict: from the ancient world to the modern Middle East (1st ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 710. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5. OCLC 617650689.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Müller, Leos (2004). Consuls, corsairs, and commerce: the Swedish consular service and long-distance shipping, 1720–1815 (PDF). Acta Universitas Upsaliensis. pp. 55–60, 70. ISBN 978-91-554-6003-7. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ a b Massengale, James (1996). "The Enlightenment and the Gustavian Age". In Warme, Lars G. (ed.). A History of Swedish literature. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 102, 104–105. ISBN 9780803247505.

- ^ Fryksén, Gustaf; Grenet, Mathieu (May 2017). Bartolomei, Arnaud; Ulbert, Jörg; Calafat, Guillaume (eds.). De l'utilité commerciale des consuls: l'institution consulaire et les marchands dans le monde méditerranéen (XVIIe-XXe siècle) (in French). École française de Rome. p. 9. ISBN 978-2-7283-1260-3. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ "From Rep. of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs". www.mfa.gov.tr. Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Müller, Leos (2019). "Swedish Trade and Shipping in the Mediterranean in the 18th Century". In Nigro, Giampiero (ed.). Reti marittime come fattori dell'integrazione Europea / Maritime Networks As a Factor in European Integration. Firenze University Press. p. 455. ISBN 978-88-6453-856-3. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Müller, Leos (2007). Swedish consular reports as a source of business information 1700–1800 (PDF). Information Flows: New Approaches in the Historical Study of Business Information (Report). Helsinki: SKS, Finnish Literature Society. pp. 255–274. ISBN 978-951-746-941-8. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ Adolf Frederick of Sweden (1738). Kongl. May:tz Nådiga Resolution Angående Sweriges Siöfart Och Handel på Levanten. Gifwen Stockholm i Råd-Cammaren, den 20. Febr. Anno 1738 (in Swedish). Transcribed by Lars Bruzelius. Stockholm: Boktryckeriet. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Bregnsbo, Michael; Winton, Patrik (2016). Scandinavia in the Age of Revolution: Nordic Political Cultures, 1740–1820. Routledge. pp. 219–223. ISBN 978-1-351-90202-1. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b Müller, Leos (7 July 2011). "Commerce et navigation suédois en Méditerranéee à l'époque moderne, 1650–1815". In Poussou, Jean-Pierre (ed.). La Méditerranée dans les circulations atlantiques au XVIIIe siècle (in French). Presses Paris Sorbonne. pp. 45–49, 52–54. ISBN 978-2-84050-755-0.